Best practices for fonts, Optimize web fonts for Core Web Vitals. Every Developers Should know about it.

Written by Appsbd Blog. Posted in Others No Comments

Font

This article discusses performance best practices for fonts. There are a variety of ways in which web fonts impact performance:

- Delayed text rendering: If a web font has not loaded, browsers typically delay text rendering. In many situations, this delays First Contentful Paint (FCP). In some situations, this delays Largest Contentful Paint (LCP).

- Layout shifts: The practice of font swapping has the potential to cause layout shifts. These layout shifts occur when a web font and its fallback font take up different amounts of space on the page.

This article is broken down into three sections: font loading, font delivery, and font rendering. Each section explains how that particular aspect of the font lifecycle works and provides corresponding best practices.

Font loading

Before diving into best practices for font loading it’s important to understand how @font-face works and how this impacts font loading.

The @font-face declaration is an essential part of working with any web font. At a minimum, it declares the name that will be used to refer to the font and indicates the location of the corresponding font file.

@font-face {

font-family: "Open Sans";

src: url("/fonts/OpenSans-Regular-webfont.woff2") format("woff2");

}

A common misconception is that a font is requested when a @font-face declaration is encountered—this is not true. By itself, @font-face declaration does not trigger font download. Rather, a font is downloaded only if it is referenced by styling that is used on the page. For example, like this:

@font-face {

font-family: "Open Sans";

src: url("/fonts/OpenSans-Regular-webfont.woff2") format("woff2");

}

h1 {

font-family: "Open Sans"

}

In other words, in the example above, Open Sans would only be downloaded if the page contained a <h1> element.

Other ways of loading a font are the preload resource hint and the Font Loading API.

Thus, when thinking about font optimization, it’s important to give stylesheets just as much consideration as the font files themselves. Changing the contents or delivery of stylesheets can have a significant impact on when fonts arrive. Similarly, removing unused CSS and splitting stylesheets can reduce the number of fonts loaded by a page.

Best practices

Fonts are typically important resources, as without them the user might be unable to view page content. Thus, best practices for font loading generally focus on making sure that fonts get loaded as early as possible. Particular care should be given to fonts loaded from third-party sites as downloading these font files requires separate connection setups.

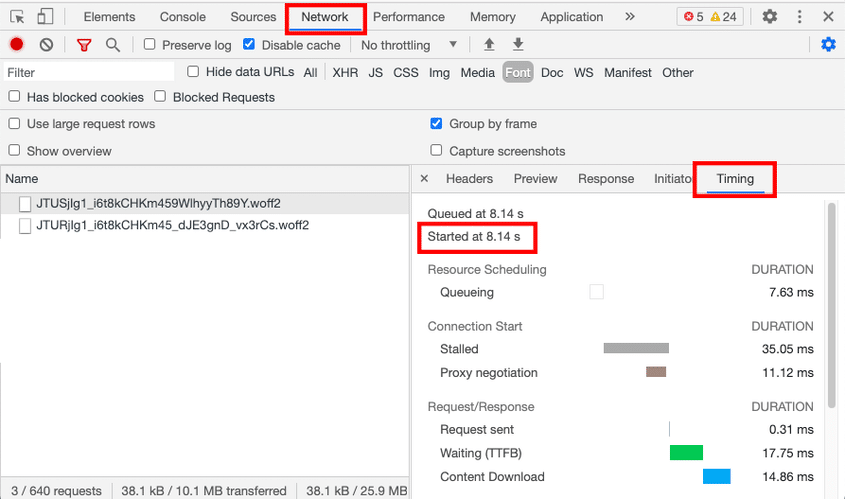

If you’re unsure if your page’s fonts are being requested in time, check the Timing tab within the Network panel in Chrome DevTools for more information.

Inline font declarations

Most sites would strongly benefit from inlining font declarations and other critical styling in the <head> of the main document rather than including them in an external stylesheet. This allows the browser to discover the font declarations sooner as the browser doesn’t need to wait for the external stylesheet to download.

<head>

<style>

@font-face {

font-family: "Open Sans";

src: url("/fonts/OpenSans-Regular-webfont.woff2") format("woff2");

}

body {

font-family: "Open Sans";

}

</style>

</head>

Inlining the font files themselves is not recommended. Inlining large resources like fonts is likely to delay the delivery of the main document, and with it, the discovery of other resources.

Preconnect to critical third-party origins

If your site loads fonts from a third-party site, it is highly recommended that you use the preconnect resource hint to establish early connection(s) with the third-party origin. Resource hints should be placed in the <head> of the document. The resource hint below sets up a connection for loading the font stylesheet.

<head>

<link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.com">

</head>

To preconnect the connection that is used to download the font file, add a separate preconnect resource hint that uses the crossorigin attribute. Unlike stylesheets, font files must be sent over a CORS connection.

<head>

<link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.com">

<link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.com" crossorigin>

</head>

When using the preconnect resource hint, keep in mind that a font provider may serve stylesheets and fonts from separate origins. For example, this is how the preconnect resource hint would be used for Google Fonts.

<head>

<link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.googleapis.com">

<link rel="preconnect" href="https://fonts.gstatic.com" crossorigin>

</head>

Google Fonts provides the option to load fonts via <link> tags or an @import statement. The <link> code snippet includes a preconnect resource hint and therefore will likely result in faster stylesheet delivery than using @import version. These <link> tags should be placed as early in the document as possible.

Avoid using preload to load fonts

Generally speaking, using the preload resource hint to load fonts should be avoided. Although preload is highly effective at making fonts discoverable early in the page load process, this comes at the cost of taking away browser resources from the loading of other resources.

In most scenarios, inlining font declarations and adjusting stylesheets is a more effective approach. These adjustments come closer to addressing the root cause of late-discovered fonts – rather than just providing a workaround.

In addition, using preload as a font-loading strategy should also be used carefully as it bypasses some of the browser’s built-in content negotiation strategies. For example, preload ignores unicode-range declarations, and if used prudently, should only be used to load a single font format.

Font delivery

Faster font delivery yields faster text rendering. In addition, if a font is delivered early enough, this can help eliminate layout shifts resulting from font swapping.

Best practices

Using self-hosted fonts #

On paper, using a self-hosted font should deliver better performance as it eliminates a third-party connection setup. However, in practice, the performance differences between these two options is less clear cut: for example, the Web Almanac found that sites using third-party fonts had a faster render than fonts that used first-party fonts.

If you are considering using self-hosted fonts, confirm that your site is using a Content Delivery Network (CDN) and HTTP/2. Without use of these technologies, it is much less likely that self-hosted fonts will deliver better performance. For more information, see Content Delivery Networks.

If you’re unsure if using self-hosted fonts will deliver better performance, try serving a font file from your own servers and compare the transfer time (including connection setup) with that of a third-party font. If you have slow servers, don’t use a CDN, or don’t use HTTP/2 it becomes less likely that the self-hosted font will be more performant.

If you use a self-hosted font, it is recommended that you also apply some of the font file optimizations that third-party font providers typically provide automatically—for example, font subsetting and WOFF2 compression. The amount of effort required to apply these optimizations will depend somewhat on the languages that your site supports. In particular, be aware that optimizing fonts for CJK languages can be particularly challenging.

Unicode-range and font subsetting: @font-face is often used in conjunction with the unicode-range descriptor. unicode-range informs the browser which characters a font can be used for.

@font-face {

font-family: "Open Sans";

src: url("/fonts/OpenSans-Regular-webfont.woff2") format("woff2");

unicode-range: U+0025-00FF;

}

A font file will be downloaded if the page contains one or more characters matching the unicode range. unicode-range is commonly used to serve different font files depending on the language used by page content.

unicode-range is often used in conjunction with the technique of subsetting. A subset font includes a smaller portion of the glyphs (that is, characters) that were contained in the original font file. For example, rather than serve all characters to all users, a site might generate separate subset fonts for Latin and Cyrillic characters. The number of glyphs per font varies wildly: Latin fonts are usually on the magnitude of 100 to 1000 glyphs per font; CJK fonts may have over 10,000 characters. Removing unused glyphs can significantly reduce the filesize of a font.

Tools for generating font subsets include subfont and glyphanger.

For information on how Google Fonts implements font subsetting, see this presentation. For the Google Fonts API subsets, see this repo.

WOFF2: Of the modern font fonts, WOFF2 is the newest, has the widest browser support, and offers the best compression. Because it uses Brotli, WOFF2 compresses 30% better than WOFF.

Use fewer web fonts

The fastest font to deliver is a font that isn’t requested in the first place. System fonts and variable fonts are two ways to potentially reduce the number of web fonts used on your site.

A system font is the default font used by the user interface of a user’s device. System fonts typically vary by operating system and version. Because the font is already installed, the font does not need to be downloaded. System fonts can work particularly well for body text.

To use the system font in your CSS, list system-ui as the font-family:

font-family: system-ui

The idea behind variable fonts is that a single variable font can be used as a replacement for multiple font files. Variable fonts work by defining a “default” font style and providing “axes” for manipulating the font. For example, a variable font with a Weight axis could be used to implement lettering that would previously require separate fonts for light, regular, bold, and extra bold.

We often refer to “Times New Roman” and “Helvetica” as fonts. However, technically speaking, these are font families. A family is composed of styles, which are particular variations of the typeface (for example, light, medium, or bold italic). A font file contains a single style unless it is a variable font. A typeface is the underlying design, which can be expressed as digital fonts – and in physical type, like carved woodblocks or metal.

Not everyone will benefit from switching to variable fonts. Variable fonts contain many styles, so typically have larger file sizes than individual non-variable fonts that only contain one style. Sites that will see the largest improvement from using variable fonts are those that use (and need to use) a variety of font styles and weights.

Font rendering

When faced with a web font that has not yet loaded, the browser is faced with a dilemma: should it hold off on rendering text until the web font has arrived? Or should it render the text in a fallback font until the web font arrives?

Different browsers handle this scenario differently. By default, Chromium-based and Firefox browsers will block text rendering for up to 3 seconds if the associated web font has not loaded; Safari will block text rendering indefinitely.

This behavior can be configured by using the font-display attribute. This choice can have significant implications: font-display has the potential to impact LCP, FCP, and layout stability.

Best practices

Choose an appropriate font-display strategy #

font-display informs the browser how it should proceed with text rendering when the associated web font has not loaded. It is defined per font-face.

@font-face {

font-family: Roboto, Sans-Serif

src: url(/fonts/roboto.woff) format('woff'),

font-display: swap;

}

There are five possible values for font-display:

| Value | Block period | Swap period |

| Auto | Varies by browser | Varies by browser |

| Block | 3 seconds | Infinite |

| Swap | 0ms | Infinite |

| Fallback | 100ms | 3 seconds |

| Optional | 100ms | None |

- Block period: The block period begins when the browser requests a web font. During the block period, if the web font is not available, the font is rendered in an invisible fallback font and thus the text will not be visible to the user. If the font is not available at the end of the block period, it will be rendered in the fallback font.

- Swap period: The swap period comes after the block period. If the web font becomes available during the swap period, it will be “swapped” in.

Recommendation #

font-display strategies reflect different viewpoints about the tradeoff between performance and aesthetics. For most sites, these are the two strategies that will be most applicable:

If performance is a top priority: Use

font-display: optional. This is the most “performant” approach: text render is delayed for no longer than 100ms and there is assurance that there will be no font-swap related layout shifts.If displaying text in a web font is a top priority: Use

font-display: swapbut make sure to deliver the font early enough that it does not cause a layout shift.

font-display: auto, font-display: block, font-display: swap, and font-display: fallback all have the potential to cause layout shifts when the font is swapped. However, of these approaches, font-display: swap will delay text render the least. Thus, it is the preferred approach for situations where it is important that text ultimately gets rendered as a web font.

Also keep in mind that these two approaches can be combined: for example, use font-display: swap for branding and other visually distinctive page elements; use font-display: optional for fonts used in body text.

The font-display strategies that work well for traditional web fonts don’t work nearly as well for icon fonts. The fallback font for an icon font typically looks significantly different than the icon font and its characters may convey a completely different meaning. As a result, icon fonts are more likely to cause significant layout shifts. In addition, using a fallback font may not be practical. If possible, it’s best to replace icon fonts with SVG (this is also better for accessibility). Newer versions of popular icon fonts typically support SVG. For more information on switching to SVG, see Font Awesome and Material Icons.